Ships of a Gold Rush

SS Central America

Discovery of gold in the western United States changed the country on multiple levels and shaped the way people perceived the west coast. Instead of a distant and mysterious area seldom visited by Easterners at the time, California became known as a place of prosperity and hope capable of forever changing lives and families. Although gold non-ferrous, it still possesses a unique magnetic quality of attracting people to its source. This is especially evident with the California Gold Rush, when many thousands of prospectors from all over the continent literally rushed west in the late 1840's searching for new found wealth and treasures.

Aspiring treasure seekers wasted as little time as possible to find their way to mining claims. The journey westward encompassed the idea of any means necessary, from wagon trails, horseback, and passenger ships. Those heading west to the land of new prosperity managed to overcome harsh conditions associated with the journey only then to be subjected to rigors of a wild mining frontier. Gold fever found a comfortable place to settle in western America as thoughts of striking it rich overnight filled the minds of men across the continent. Success of the first prospectors who landed in California in 1848 quickly grabbed news media attention. Mass migration swept the land by 1849, after multiple headline stories proclaimed lucrative discoveries of gold in California, and as much as fifty million worth pumped into the economy each year during the rush.

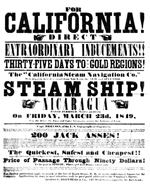

With over hundred-thousand people migrating each year, the hundred and forty day wagon trips were too slow to keep pace with demand and faster routes were reasonably desired. The majority of adventurers chose to travel over a much shorter time period on forty day paddle-wheel steamer routes with a short land jaunt at the end. Steamships became a preferred method for reaching the west coast and also provided a means for establishing infrastructure which would connect the relatively unexplored west with business operations in the east. Although steamships are attributed for transporting the majority of folk to California during the gold rush, traditional sail powered ships were still largely in operation and carried many thousands in their own right. Sail, steam, and hybrid powered ships traveled along the east coast around Florida and through the Gulf of Mexico to Panama capitalizing on the opportunity.

The land pass from Panama across Central America involved dangers of trekking through dense jungle, but it remained the quickest route provided a ship was available to take passengers up the west coast upon arrival. Trouble taking the land shortcut is one reason why some ships decided to skip the Panama pass altogether with a route heading around South America, crossing Cape Horn, and then back up the west coast to San Francisco. Prospectors could reach San Francisco in thirty to ninety days via this route provided there were no complications though Cape Horn or run-ins with pirates along the way. During the rush, gold in California was ever abundant, and many prospectors found fortunes of a lifetime in the hills, but what happened to the gold extracted at the time? We know part of it stayed in California to be minted, and also, a portion used for trade amongst prospectors and proprietors to keep operations running. The remaining treasure, to a historical understanding, traveled to New York for minting in Philadelphia with a portion traveling to London, England for processing.

Gold valuables retrieved from California moved home with prospectors or direct to processing facilities by way of contract workers on return trips. Those returning often traveled from San Francisco to Panama City, then crossed to board a ship en-route to New York. Many prospectors likely reveled in their new-found wealth on the return voyage, and probably kept an ever watchful eye on their caches throughout the long journey back to New York. In the fall of 1857, a cargo transport side-wheel steamship aptly named SS Central America, and its crew of one hundred followed a most regular routine; securing thirty-thousand pounds of California gold along with almost five hundred passengers returning to New York.

Patrons considered this a favorable time to travel, and excitement on the steamer must have created a wonderfully pleasant atmosphere to travel by. With only a few short hours remaining in the trip, the atmosphere on-board was about to change. The steamship approached the coast of South Carolina, right into the path of a category two hurricane. The storm swooped around, trapping the SS Central America in high winds and rough seas. Gales ripped the sails apart and sprayed large amounts of water off swelling wave crests on deck. The spray and crashing waves became too much for the steamer to handle, the ship's holds were soon overflowing, and threat of sinking is now very real. Excess water in the holds snuffed out the boiler, and without sails to push away with, the Central America was sucked deeper into the storm.

Captain William Lewis Herndon and a distraught crew in full-fledged emergency protocol, fighting desperately for the lives of hundreds of people. Among the chaos, the ship's flag hangs upside down acting as a distress beacon, eerily symbolic of the steamer's inevitable fate. Able passengers and crew frantically worked through the night bailing water, trying to get the boiler running once again, and to save everyone from disaster. Almost a day into distress efforts, a small West Indian brig by the name of Marine met up with the SS Central America with some much needed relief.

By this time, chances of restarting the boiler were next to impossible, and the outcome became all too apparent, the SS Central America had reached the rope's end. In a noble act, Herndon personally helped evacuate over one hundred and fifty women and children onto the Marine, packing it beyond capacity. He then waited on the Central America with his crew and remaining passengers for future rescue. Agonizing hours passed with no sign of help, not a hope in the distance. Water continued filling the holds far too quickly to compete with, and time ran out. SS Central America along with its captain, crew, four hundred passengers, and thirty-thousand pounds of California gold sunk to the sea floor. As news reached home, families and loved ones of returning prospectors were absolutely devastated.

A developing American economy depending on wealth from the gold rush was also affected by the significant loss. It's theorized this tragedy contributed on some level to the Panic of 1857, the first world-wide economic crisis. With no way to find or recover the SS Central America, it unfortunately became forgotten and lost on the ocean floor. Nearly a century and a half later, the crushing, heartfelt story of the noble Captain Herndon, and lost wealth from the California Gold Rush, would resurface into public media once again. In 1987, the wreck of the SS Central America was discovered off the coast of South Carolina at a depth of seventy-two hundred feet, incredibly far deeper than previously imagined. To this day, recovery operations with modern technologies have salvaged roughly twelve-thousand pounds of gold so far, to a sum of almost hundred and fifty million dollars worth. The remaining Gold Rush treasure, some eighteen-thousand pounds, slightly over three-hundred million worth, has not been located.